Thixotrophy

Clay is all around us. We walk on it, we use it in our homes and we build with it. A number of elements are required to work with the material; elements that stabilize it or make it more volatile; elements that can add colour, texture or tone. The raw clay itself is in an ever-changing state of fluidity. Thixotropy is the suspension of particles in the clay to control the fluidity. This is important, because without adding elements to the clay, it will not support itself or form a strong bond. In fact, only under stress, or agitation, does the clay retain its fluidity.

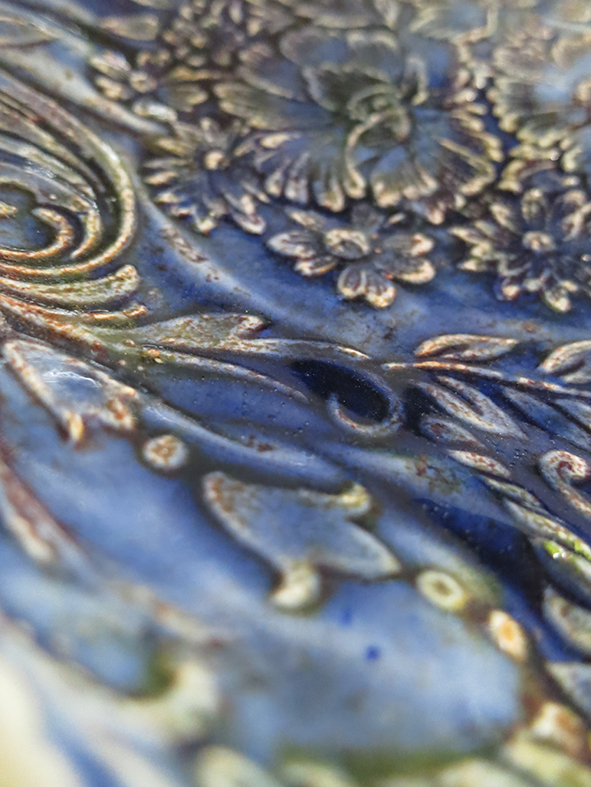

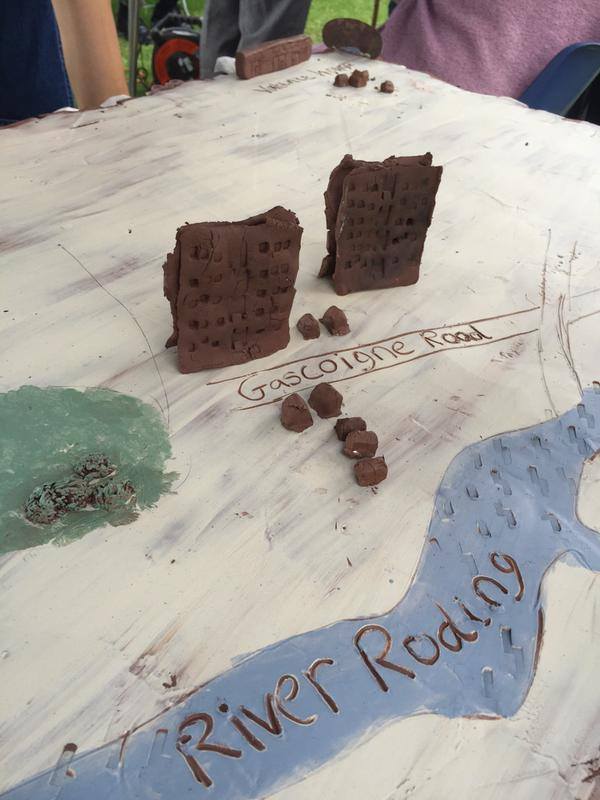

Thixotrophy is an artwork that reflects the environment in which it was made; it is the flow and movement of particles or energy across a given area. The objects were cast in liquid clay and designed to increase the notion of fluidity with residents helping to turn wet plaster into unique forms with multiple facets. Volunteers, schoolchildren and construction workers also helped to dig clay out of the ground and filtered it to remove unwanted minerals. The clay was dried out, stained with colour and water then added back into the mix. This unique Gascoigne clay was added to the forms to provide the textures and colour so frequently used to describe the lively community of Gascoigne.

Fluidity is a concept I return to whenever I come back to the estate. People move in. People move out. Kids are ever-present one week, and nowhere to be seen the next. Fluidity is in the open spaces occupied by the different users of the estate. It changes from morning to night, from weekday to weekend. The conversations and interviews of past and present residents reveal an estate that has dealt with many periods of upheaval including multicultural integration, political interventions and numerous housing policies. But the residents, young and old, look back with fondness and continue to look forward in hope. Much like the environment of the Gascoigne Estate, there are many ways to control, contest and interpret the surface tension of clay. The question I often ask myself is: how much influence do I have over the process, and how much is being driven by the material itself? Residents may pose the same question about the future of their estate. Simeon Featherstone

Gascoigne Craft Laboratory

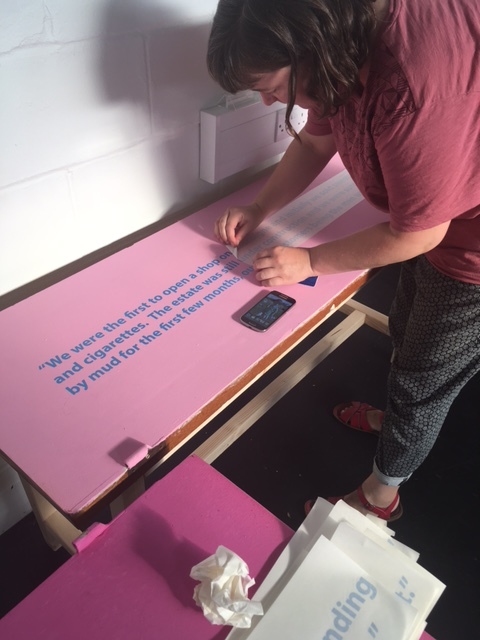

Damien Robinson, Delyth Taylor and Simeon Featherstone of Parasite Ceramics took up residency at the Gascoigne Living Museum for the Open Estate programme with support from local volunteers and project officer, Steve Lawes. The shop became a base for many meetings, workshops and children’s activities over the course of a year. The former job shop provided the residents with cups of teas and somewhere to reflect on their own surroundings through creativity and discussion.

The contents of the Laboratory and Cabinet of Travelling Treasures are locally sourced objects, donations from residents or artworks made by the community. These included drawings, plaster models, clay sculptures and many other processes that helped to develop the artwork for the Open Estate Festival. Children used the plaster lathe for the very first time, parents made collages to suggest colour and pattern, and clay was pressed into different surfaces around the estate. The artwork itself has been a long process of working the local clay into a manageable material. The Gascoigne Laboratory and Cabinet of Travelling Treasures documented this creative journey and paid tribute to the community of Gascoigne for all their input and enthusiasm during the Open Estate programme.